Autonomous Vehicles Aren’t Human

Published:

On Saturday at the IC2S2 conference, I saw a presentation about the decisions people would like autonomous cars to make when faced with moral dilemmas. Since then, I have seen quite a bit of coverage on the Science article by the same team.

The anthropomorphic assumption

There is an assumption in the paper, and in most of the coverage, that the designers of driverless cars will eventually have to make Trolley problem decisions, and explicitly encode the relative “value” of people, by telling the cars which people to run into in unavoidable crashes. Much of the paper focuses on the way respondents reply to these sorts of dilemmas (e.g, Should the car run into 3 young people or 4 old people? A father of 2 or a pregnant woman?, etc.).

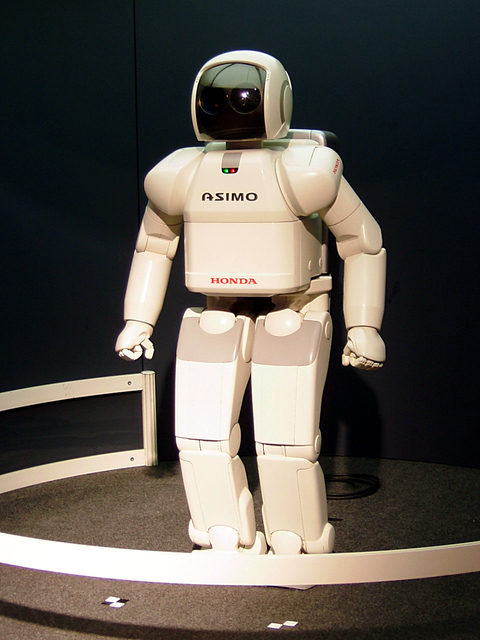

While it is certainly interesting to know how people feel about these dilemmas in this context, this line of research displays an anthropomorphic assumption toward understanding autonomous cars, and artificial intelligence more generally. The assumption is that if computers are able to do something that we can do (like drive a car), then they must be doing it in a way that’s similar to how we do it. However, autonomous cars are not people. The algorithms behind the driverless car are trained on lots of data about the tasks related to driving a car: how to accelerate, decelerate, and turn, how to identify road signs and street markings, and how to identify and avoid things you might run into or which might run into you. To fulfill the goal of not running into stuff, a car may need to understand the different acceleration profiles of cars, bikes, deer, and pedestrians, but it doesn’t need to understand anything about them – that is, it doesn’t need to be trained to understand that bicycles are ridden by humans, or that deer are mammals. There is certainly no reason to train a car to distinguish between young pedestrians and old pedestrians, or men and women.

Computer cognition is limited

Our human cognition can identify humans and make moral calculations “for free”. When we are driving, we cannot help it. However, when we think about the actual engineering that goes into making driverless car algorithms, we would have to program cars to use some of their computational power to have these skills. The assumption of the paper is that designers would simply need to plug in the relative value of different scenarios. In reality, we would need to train cars to continuously identify everything around them, and attach a “moral value” to each object, just in case they are put into a situation where they are 1) forced to crash and 2) still have enough control to crash into what they want. Indeed, it seems much smarter to use those computational resources to do even more to try to avoid a crash in the first place.

Algorithms are tools

Now, it’s important to recognize that choosing not to program autonomous cars with these abilities is itself a moral decision: when cars are in a situation where they have to crash, they will make the decision that is most likely to avoid the crash, even if that makes it more likely that they will hurt or kill the “wrong” people. This is how tools work, though. We don’t expect knives to only cut fruit but not fingers. Autonomous cars are also tools, and even though they are doing something that people also do, there is no reason to expect that they will ever have to make the sorts of moral decisions that people do.